|

| Elizabeth Báthory, Lady of Cachtice |

Countess Elizabeth Báthory was born in the Kingdom of

Hungary, Habsburgh Monarchy, in 1560. She was a member of the Báthorys, one of

the most powerful dinasties in the region. She was the niece of Stephen Báthory,

the king of Poland and grand duke of Lithuania as well as prince of

Transylvania. Despite this aristocratic background and wealth, the clan was

feared for its cruelty, and some of Elizabeth’s relatives created a dark legend

around their figures. For instance, Lady Klára Báthory, Elizabeth’s aunt on her

father’s side, ‘‘has been remembered in the histories as an insatiable bisexual

adventuress’’ (Thorne 147), and the person who may have introduced Elizabeth

into sadomasochism. When Klára was caught red-handed with one of her lovers,

legend has it that ‘‘Klára’s punishment was to be raped by every member of the

Turkish garrison in turn’’ (Thorne 147). Therefore, the brutal violence of the

age did not soften the Countess’s future cruel behaviour which this post will

examine. Another grim tale narrates how Elizabeth’s brother, Stephen, was

thought to be an alcoholic, a lecher and a lunatic (Thorne 149).

Mental disorders in the family may be the result of the

inbreeding among the kin, since they did not wish their blood to be fused with that

of others. Elizabeth is thought to have suffered from epilepsy and to have been

deranged. As the Countess is the most notoriously remembered of the Báthorys,

this blog post will analyse her figure from a vampiric perspective. This general

approximation to her persona focuses on the belief that she murdered more than

650 young girls. The reason allegedly given as justification for her atrocious

crimes was to obtain blood from the

virgins in order to restore her youthfulness. She was condemned for her crimes

and imprisoned in her own castle, where she died in 1614. Her character has

inspired many varied narratives, yet my text will focus on three literary

sources which will help to study the Countess from a Jungian viewpoint: the

stepmother of Brother Grimm’s ‘‘Little Snow White’’ (first published in 1812),

the vampire Carmilla in Sheridan Le Fanu’s eponymous novella (1871-1872), and Argentinian

poetess Alejandra Pizarnik’s La Condesa

Sangrienta (The Bloody Countess) (1965).

Elizabeth

in the Bloodthirsty Stepmother of ‘‘Little Snow White’’

In the famous fairytale of ‘‘Little Snow White’’, the

Grimm Brothers depict the consequences extreme vanity can trigger. Both the

stepmother as well as Snow White emphasise the relevance of being young and

beautiful. Vanity is a trait present in Countess Báthory, and this first

section of the blog post will explore the existing connection between the tale

and the aristocrat’s life.

|

| Illustration of Snow White's stepmother by P.J.Lynch |

The stepmother embodies jealousy and envy towards the

young girl for her beauty. With her continuous demanding ‘‘Mirror, mirror on

the wall, who in this land is fairest of all?’’ (Jacob and Wilhem Grimm) and

her contempt towards the young princess, the adult woman personifies what,

according to Jung’s theory, is named the ‘‘Shadow’’. Swiss psychiatrist and

psychoanalyst Carl Jung considered that humans share a ‘‘collective

unconscious’’ in which instincts and archetypes are common to different cultures.

Thus, concepts such as hell appear in distinct traditions. Jung’s archetype of

the ‘‘Shadow’’ stands for the ‘‘dark side’’ of a person, the unconscious

negative aspects of the self. Jungian expert June Singer differentiates between

the ‘‘Great Mother’’ of the Ego from the ‘‘Terrible Mother’’ in the ‘‘Shadow’’.

Consequently, Grimm’s stepmother embodies the evil side of motherhood

attempting to control the virtuous Snow White. Elizabeth Báthory is also

associated with vanity and mirrors. During the trial against the Countess which

Palatine of Hungary George Thurzó arranged, Ficzkó, one of her loyal

assistants, described his mistress ‘‘as using her mirror to ‘beseech’ – to call

up spirits , cast spells or ask for supernatural help, and gives details of the

ritual preparation of the deadly cake, although he does not explain how

Elisabeth could have sent it to the intended victims or persuaded them to eat

it’’ (Thorne 44). If we consider the stepmother summoning the spirit of the

looking glass to verify who the most beautiful female is, and how she employs

an apple to lure her victim and destroy her, a parallel between the stepmother

and the Countess is clearly drawn.

Furthermore, Shuli Barzilai explains how professors

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue that both characters in the fairy tale

represent ‘‘dissociated parts of one psyche. In terms of the Jungian symbology

suggested by their analysis, Snow White and the queen constitute a house

divided against itself: ‘‘Shadow fights shadow, image destroys image in the

crystal prison, as if the ‘fiend’…should plot to destroy the ‘angel’ who is

another one of her selves’’’’ (Barzilai 520). In the Countess’s case, her

basement at her Čachtice castle is

unmistakably her space of action. Her prey were mutilated, tortured and drained

of their blood in this location with the aid of her servants. On the one hand,

she may have chosen her basement to torture her victims as a means to hide her

misdeeds; on the other hand it is significant that an underground room

corresponds to her ‘‘underworld’’, a journey into her excessive subconscious. Elizabeth,

aided by her servants, was able to mistreat the girls she wished to since she

was isolated in her castle too. She lured them to her fortress as ‘‘it was a

great honour for a girl to be given a position in her (Elizabeth’s) household,

even that of a humble seamstress or chambermaid, and all her servants had come

recommended for a particular skill’’ (Thorne 31). However, the rumours of her

cruelty spread and ‘‘poor families around Čachtice hid their daughters when they heard that the Lady was

approaching’’ (Thorne 31).

|

| Carlos Schwabe's illustration for Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal, 1900 |

In time, the Countess became bolder, and she began to

attack noblewomen, which led her to her final destruction. Married to Count

Francis Nádasdy at the age of 15, her husband left for the war and was hardly ever

with his family. Therefore, Elizabeth was unreservedly in charge of their state,

which she managed perfectly. This function was mainly undertaken by men at her

time. Notably, in the Grimm’s tale Snow White’s father is mainly absent; he

only appears at the beginning of the story, when his wife dies and a year later

he takes a new wife. Therefore, the non-appearance of the father figure to

protect Snow White facilitates her stepmother’s assault.

Nonetheless, it is remarkable that in the first

versions of the tale, it is the real mother and not Snow White’s stepmother who

aims to eliminate her. ‘‘Only with the nineteenth-century German reworking and

editing of the tale was the mother definitely recast as a stepmother’’

(Barzilai 526). This means that the stepmother is seen as an Other inside the

family circle. ‘‘The stepmother represents feared social forces that threaten

to destabilize imaginary family and national bonds established through an

ideology of biological sameness’’ (Hewitt-White 121). It is due to the

Christian values of their time, that the Grimm brothers recognise virtue as

inherent in natural lineage. Elizabeth was not the mother of the youngsters she

murdered, yet ‘‘she was related by blood or marriage to nearly all the victims

named in the testimonies’’ (Thorne 31). Therefore, the idea of evil inside the

family bond emerges in the Countess’s massacres.

Some authors do not only describe this link of ‘‘blood’’

as a means to illustrate anxieties between mother/stepmother and daughter; they

also perceive ‘‘considerable kinship with vampire lore, including that of

Elizabeth Báthory’’(Kord 76). Furthermore, the Grimms had written a fragment named

‘‘Nach Einem Wiener Fliegende Blatt’’, ‘‘a play on words which can mean ‘‘a Flying

Leaf’’, ‘‘a Handbill’’ or ‘‘a Rumour on the Wind…from Vienna’’, with which ‘‘the

Brothers Grimm referred to a seventeenth-century folktale telling of an unnamed

Hungarian lady who murdered eight to twelve maidens’’ (Thorne 205). Certain scholars consider Snow White to be the

vampire since she is ‘‘as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as ebony

wood’’ (Grimm) as well as her condition of sleeping in a coffin and not aging,

yet the figure of the wicked queen can also evoke vampirism. Various versions

of the tale emerge in different cultures previous to the famous adaptation by

the Grimms, and they depict ferocious actions. When the stepmother orders the

hunter to slaughter the princess, the reworkings of the story become gory:

Whilst in the Grimm’s edition the hunter must bring Snow White’s lungs and

liver to the stepmother, ‘‘in Spain, the queen is even more bloodthirsty,

asking for a bottle of blood, with the girl’s toe used as a cork. In Italy, the

cruel queen instructs the huntsman to return with the girl’s intestines and her

blood-soaked shirt’’ (Tatar). These signs of cruelty also occur in Báthory’s cannibalism,

as narrated by Ponikenus, a reverend known to Elizabeth: ‘‘We heard from those

maids who are still living that they were forced to eat their own flesh, which

was fried on an open fire. The flesh of other maids was chopped and mashed, as

with mushrooms in the preparation of a meal’’(Thorne 73).

Nevertheless, torture was not the only treatment the

Countess meted out to her young victims. She is famous for her bisexual affairs

and the following section of the blog will focus on Elizabeth’s sexuality and

how it may have influenced one the most relevant novellas in Gothic fiction:

Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘‘Carmilla’’.

Carmilla

as an embodiment of Elizabeth

In 1872 Irish Gothic writer Sheridan Le Fanu published

his story ‘‘Carmilla’’ in a serial

titled The Dark Blue. The tale is

narrated by Laura, a young motherless girl who lives in isolation in a castle in Styria with her father, some governesses, and some

servants. The girl is disappointed when an expected visit by her father’s

friend General Spielsdorf and his niece is postponed. The General, whose

intention was to stay with the family, explains to Laura’s father that his

young relative had suddenly become ill and died. Therefore, Laura’s wish to

gain a friend is thwarted. Nevertheless, an accident occurs, and a youngster

enters their lives: the apparently naïve Carmilla, who in truth is a vampire.

Carmilla lures Laura to her by means of her beauty: ‘‘Her complexion was rich

and brilliant; her features were small and beautifully formed; her eyes, large,

dark and lustrous; her hair was quite wonderful’’ (Le Fanu 26). Le Fanu’s

choice of setting of his novella as well as the accentuated allure of his

predator echo Báthory’s persona, although the Countess is not presented as an

innocent creature, but as a seductress whose aim is to murder. R. A. von

Elsberg is the first author to describe Elizabeth’s appearance in his 1894 Die Blutgräfin when he refers to Báthory’s portrait:

‘‘She is Elisabeth Báthory, but is she at the same

time the tigress? She is a lady of high rank with a cultivated mind, but her

great eyes let us see deeper within to her devilish passion. Her finely

chiselled nose, her wilful and obstinate lips show her siren-like personality,

her wild heart…long white hands and in contrast to her white skin, her black

hair: these are the features which definitely define her difficult nature’’

(Thorne 120).

|

| Illustration for ''Carmilla'' by David Henry Friston |

The eponymous Carmilla also belongs to the

aristocracy, and her hidden bloodthirst emerges as the plot develops. Besides, the

story relates how Carmilla and Laura belong to the same lineage. Le Fanu

‘‘makes vampirism, incest and homosexuality resonate’’ (Leal 38-39) in his

tale. Whilst ‘‘several critics have noted how Carmilla is a rendition of Coleridge’s fragment ‘‘Christabel,’’

which also features a female vampire, a motherless victim, obscure familial

ties, and same-sex desire’’ (Leal 39), Coleridge names one of his characters

from his play Zápolya ‘‘Bethlen

Báthory’’, ‘‘an amalgam of Elisabeth Báthory’s nephew Prince Gábor and his

successor, Gábor Bethlen’’ (Thorne 8). Therefore, the Romantic poet may also

have been aware of the figure of the Hungarian Countess and her legend.

Jung ‘‘reasons that within the collective unconscious

(that part of the unconscious that is inherited and identical in all humans) of

both males and females there lies an element of the opposite sex’’ (Stupaks 1).

Males possess a feminine element named ‘‘anima’’ and females a masculine

element called ‘‘animus’’. According to Jung, animus-inflated women tend to

develop an exceptional rational instinct. Carmilla, as well as Elizabeth,

represents the Jungian archetype of the fatal seductress, the Temptress; they

both embody an active ‘‘shadow’’ of the personality, which needs to have power

over their prey by using their physical presence until they no longer maintain

any interest in their victim, who is male. Both Carmilla and Báthory are, thus,

manipulative and methodical, yet the main difference is that the victims are

young girls. In reality, Elizabeth’s sexual behaviour is not reported, yet,

from her position of complete power after the death of her husband in 1604, she

was able to obtain whatever she wanted (Thorne).

When Carmilla attacks Laura, she turns into a cat:

‘‘But I (Laura) was equally conscious of being in my room, and lying in bed, precisely

as I actually was… I saw something moving round the foot of the bed, which at

first I could not accurately distinguish. But I soon saw that it was a

sooty-black animal that resembled a monstrous cat’’ (Le Fanu 45). Carmilla here

echoes Báthory, since shapeshifting was believed to be real during the

Countess’s time, and the Countess was credited with the ability to summon evil

creatures in order to defeat her powerful enemies. Pastor Ponikenus, the

Palatine’s ally, claimed that Elizabeth was a sorceress and noted these words

as hers: ‘‘God help! God help! You little cloud! God help little cloud! God

grant, God grant health to Elizabeth Báthory. Send, send me little cloud ninety

cats, I command you, who are the lord of the cats… send them away to bite King

Matthia’s heart, to bite my lord Palantine’s heart…’’ (Thorne 71).

Interestingly, the King owed Elizabeth money, and the Palatine

Thurzó initiated the trial against her, accusing her of mass murder, witchcraft

and high treason. Báthory was walled up in her castle till her death and her lineage

ended once her nephew Gábor Báthory was murdered. Similarly, vampire Carmilla,

whose real name is Countess Mircalla Karnstein, is finally defeated in her

coffin full of blood and, consequently, her direct dinasty, although present

with descendants such as Laura, becomes extinct.

The fact that Mircalla rests in her blood-filled tomb

and maintains her youth resembles Widow Nadashy’s legend of her notorious gore

baths: ‘‘Two old women and a certain Fitzko assisted her in her undertaking.

This monster used to kill the luckless victim, and the old women caught the

blood, in which Elizabeth was wont to bathe at the hour of four in the morning.

After the bath she appeared more beautiful than before’’ (Sabine Baring-Gould

139-140). In reality, Báthory’s blood-bathing first appeared in Jesuit Turóczi

László’s Tragica Historia in 1729.

There is no mention of this practice in the trial against the aristocrat.

|

| Báthory depicted by Hungarian Impressionist István Csók, 1893 |

There are more similarities between Le Fanu’s vampire

and the Countess: where Báthory is aided by her servants, Carmilla has the support

of two women: the so-called Countess who introduces the vampire to her victims,

and the mysterious woman of the carriage who does not get out of it (Le Fanu

18-19). This lady resembles Báthory’s confidante Anna Darvulia, ‘‘the Lady’s

guide and inspiration in her torturing’’(Thorne 98), who was in charge of

Elizabeth’s domestic arrangements from around 1595 and who died before the

trial against the aristocrat.

The association between sorcery and vampirism is

significant in Carmilla: Countess

Karnstein instantly purchases ‘‘oblongs slips of vellum, with cabalistic

ciphers and diagrams upon them’’ (Le Fanu 32) as an ‘‘amulet against the

oupire’’ (32). Similarly, in Hungary, aristocratic women such as Elizabeth,

even though they were not be sorceresses themselves, they could act as

protectors of the crones known for their healing skills. Nevertheless, when one

of the remedies did not work and disease spread uncontrollably, hysteria ruled

and between 1529 and 1768 witchcraft trials took place in Báthory’s country.

Besides, in her case, it is worthy of notice that she was a Protestant, and she

created enemies with other faiths, especially Catholics. Religion also relates

Carmilla’s lack of prayers to her scorn towards her labourer victims. When the

funeral of a young girl occurs in front of Laura and Carmilla, the vampire

claims: ‘‘She? I don’t trouble my head about peasants. I don’t know who she

is…’’, and she continues… ‘‘Well, her funeral is over, I hope, and her hymn

sung; and our ears shan’t be tortured with that discord and jargon’’ (Le Fanu

30-31).

Similarly, Báthory despises peasant girls to the point

of torturing them to death. Or so does her notorious legend declare. Alejandra

Pizarnik’s dark collection of poetic prose on the Countess describes in detail

the alleged torment the Lady imposed on her prey. The last section of the blog

will examine The Bloody Countess.

Elizabeth’s Torture in Alejandra Pizarnik’s La Condesa Sangrienta (The Bloody Countess)

Alejandra Pizarnik narrates Báthory’s life in her

short book The Bloody Countess. Following French surrealist author Valentine Penrose’s 1962 Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante, the Argentinian combines

poetic prose, dark fantasy and journalism to depict the legend of the notorious

Countess. Pizarnik focuses on the alleged torture which the aristocrat perpetrated

to obtain eternal youth through blood from the very beginning of her narrative.

Pizarnik briefly analyses how Penrose describes the Countess as a ‘‘gorgeous’’

criminal : ‘‘she (Penrose) inscribes the subterranean kingdom of Elizabeth

Báthory in the torture room of her medieval castle : there, the sinister beauty

of the night creatures summarises itself in a silent woman of a legendary

paleness, of demented eyes, of hair with the luxurious colour of the crows ’’[i] (Pizarnik). Although

Báthory employed different methods of torture, such as placing girls inside a

cage with spikes, or throwing frozen water at their naked bodies outdoors in

winter until they died, this last section will examine Pizarnik’s allusion to

the Iron Virgin.

Pizarnik begins each of her chapters with quotes which

give a hint of the subject treated in her narrative. Yet there is an author

whom she not only cites, but whom she also comments on at the end of her work,and

mentions alongside the Baron and serial killer of children Gilles de Rais:

French writer and libertine Marquis de Sade.

Sadism was named after the French author, and definitively

established as a term by Freud in his 1905 Three

Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. For French philosopher Michel Foucault,

‘‘Sadism is not a name finally given to a practice as old as Eros; it is

a massive cultural fact which appeared precisely at the end of the eighteenth

century, and which constitutes one of the greatest conversions of Western

imagination: unreason transformed into delirium of the heart, madness of

desire, the insane dialogue of love and death in the limitless presumption of

appetite’’(Foucault 199).

Consequently, Pizarnik wisely compares the Countess to

Sade and de Rais, since Báthory may have suffered from Sadistic personality

disorder, as it was named in an appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R), yet removed from later versions of the

manual. The disorder involves obtaining sexual pleasure from the discomfort or

pain of others (Myers 2006).

The Argentinian author first explains the Iron Virgin:

‘‘There

was a famous automat in Nuremberg named ‘‘the Iron Virgin’’. Countess Báthory

acquired a copy for the torture room of her castle in Csejthe’’ (Pizarnik). The

‘‘Nuremberg Virgin’’, also known as ‘‘the Iron Maiden’’, ‘‘is often linked to

the Middle Ages, though there is reason to believe that, in fact, it was not

conceived until the end of the XVIII century’’ (Torture Museum). The most

famous one is the one in Nuremberg, Germany. It consists of a womanlike sarcophagus

‘‘with a virgin Mary placed on top by the inquisitors’’ (Torture Museum) and

with spikes which stab the arms, legs, stomach, eyes, shoulders and buttocks of

the person placed inside. Pizarnik describes the beauty of the automat,

‘‘naked, with jewellery on, with blonde hair which reached the floor’’

[ii]and compares it to the one

of the virgins: ‘‘the automat holds her (the victim) and thus nobody will be

able to untie the living body from the iron one, both equal in beauty’’[iii]. Meanwhile, the

aristocrat, sitting on her throne, observes (Pizarnik).

|

| Santiago Caruso's illustration for Alejandra Pizarnik's The Bloody Countess |

The use of the Iron Virgin can be associated with

Irish writer Bram Stoker’s short story ‘‘The Squaw’’, first published in 1893 in the British

magazine Holly Leaves the Christmas Number of the Illustrated Sporting

and Dramatic News. In this tale, a couple go for their honeymoon to Germany, where they

meet an American tourist, Elias P. Hutcheson. They decide to visit the

Nuremberg castle together. On the way there, they see a cat with her kitten.

Hutcheson decides to throw a pebble near them to see their reaction, but the

stone hits the kitten’s head and kills it. Its mother enraged starts following

the protagonists. Even though Amelia, the protagonist’s wife, suspects that the

cat’s intention may be to kill Hutcheson if it could, the American jokes about it

and narrates to them a similar situation he experienced in the USA, where an

Apache woman’s child was killed by a soldier and she tortured him to death.

There is a moment in the story, when the three main characters enter the

Torture Tower of the castle in which an Iron Virgin is placed. The American

tourist claims that he wishes to enter the automat as the people who suffered

it did, and he pays the custodian some money to allow him to get inside it with

his hands and feet tied. The narrator remarks how ‘‘he seemed to really enjoy

it’’ (Stoker 10), and Hutcheson boasts how he ‘‘spent a night inside a dead

horse’’ (Stoker 9). The cat emerges, attacks the custodian maintaining the rope

of the machine, the man drops it and the American dies. Consequently, ‘‘he who

killed the mother cat’s baby is killed by the mother cat when he is the baby inside

of the Virgin’’ (Bierman 171). Elisabeth may have murdered more than 650 babies

this way, yet none of her victims had previously harmed her.

Not only the Iron Virgin, but also the use of cats as agents of murder connect Báthory to Stoker’s story. Also, the aforementioned detail of the American sleeping inside a horse echoes the execution of a gypsy Elisabeth witnessed as a pubescent, in which ‘‘a horse was disembowelled and the gipsy forced into its stomach, which was then sewn up, leaving him to die slowly inside the putrefying carcass’’ (Thorne 4). There may be, thus, echoes of the Countess in this story apart from in Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a novel in which the vampire is a Count, not a Prince as Romanian Vlad III Dracula (1428/31- 1476/77) was, and he lives alone in his castle, as Báthory did. Báthory was an admirer of Vlad the Impaler’s methods of torture (Thorne), though impalement has never been mentioned as a technique of hers.

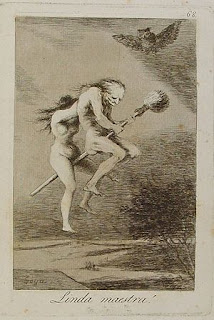

The

beauty of the criminal and her machine to torture clashes with the hideousness

of Báthory’s servants. Pizarnik explains how Elisabeth was helped by ‘‘her two old maids, both

escaped from a painting by Goya: the dirty, smelly, incredibly ugly and

perverse Dorkó and Jó Ilona’’[iv]

(Pizarnik). Moreover, the witch Darvulia was the cruellest of them.

|

| Goya's Pretty Teacher!, Capricho 68, 1797-1799 |

Goya emerges in Foucault’s theory

of madness in which the abovementioned Sade is also present: ‘‘ They (the Caprichos, etchings and aquatints by the Spanish painter done in 1797 and 1798)

are premissed on the describabilty of madness. Madness here is a nightmare. ’’

(Boyne 25). Foucault compares Goya’s images to Sade’s 1791 novel Justine, which narrates the harsh life of the eponymous protagonist from the

age of twelve until she is twenty-six, and which emphasises sexual perversions and

abuse. Boyne analyses how ‘‘Just as Goya’s Caprichos illuminate the horror of natural multiplicity, so in de Sade’s Justine

we are presented with the vicissitudes of a hydra-headed desire which, after

all, was given to humankind by nature itself’’ (25-26). Pizarnik agrees with

this conclusion since at the end of her work, she states that ‘‘she (Báthory) is another proof that the total

freedom of the human creature is horrible’’[v] (Pizarnik).

It is probable that we will never

be able to know what really occurred at Čachtice castle due to the

difficulties in finding documents, and the language barrier that emerges for

most scholars, yet fiction and non-fiction continue to depict and analyse the

haunting figure of the mysterious Countess. This blog has studied her presence

in various narratives, beginning with the popular fairytale of ‘‘Little Snow

White’’ by the Brothers Grimm, to

afterwards illustrate Sheridan Le Fanu’s vampire novella ‘‘Carmilla’’ and,

finally, examine Alejandra Pizarnik’s rough text about Báthory’s torture. A

Jungian approach has been introduced in the first two sections of the post to

capture Elizabeth’s personality as well as why she has been so present in vampire literature.

[i] Original texts: '‘Inscribe el reino subterráneo de Elizabeth Báthory en la sala de

torturas de su castillo medieval: allí, la siniestra hermosura de las criaturas

nocturnas se resume en una silenciosa palidez legendaria, de ojos dementes, de

cabellos del color suntuoso de los cuervos'’.

[ii] ‘‘Desnuda, maquillada, enjoyada, con rubios

cabellos que llegaban al suelo’’

[iii] ‘‘La autómata la abraza y ya nadie podrá

desanudar el cuerpo vivo del cuerpo de hierro, ambos iguales en belleza’’.

[iv] ‘‘Sus dos viejas sirvientas, dos

escapadas de alguna obra de Goya: las sucias, malolientes, increíblemente feas

y perversas Dorkó y Jó Ilona''.

[v] ‘‘Ella es una prueba más de que la

libertad absoluta de la criatura humana es horrible’’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Baring-Gould, Sabine, The Book of Were-wolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition,

https://archive.org/details/bookwerewolvesb00barigoog

(Accessed 10th March 2018)

Barzilai,

Shuli, ‘‘Reading ‘‘Snow White’’: The Mother’s Story’’, Signs, Vol. 15, No. 3, The Ideology of Mothering: Disruption and Reproduction of Patriarchy

(Spring, 1990), pp. 515-534 http://kmcglaughlinhbhsenglish.edublogs.org/files/2011/12/Reading-Snow-White-The-Mothers-Story-15w2i2c.pdf

(Accessed 19th March 2018)

Biergman, Joseph. S., in Bram Stoker: History, Psychoanalysis and the

Gothic, by Smith, Andrew and Hughes, William (Palgrave Macmillan, 1998)-via

Google Books

Boyne, Roy, Foucault and Derrida: The Other Side of Reason (Routledge, 2013)-

via Google Books

Foucault, Michel, Madness and Civilization: A History of

Insanity in the Age of Reason (Routledge Classics, Psychology Press,

2001)-via Google Books

Grimm, Jacob

and Wilhelm, ‘‘Little Snow White’’, http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm053.html

(Accessed 20th March 2018)

Hewitt-White, Caitlin, ‘‘The

Stepmother in the Grimm’s Children’s and Household Tales’’, https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/view/1920

(Accessed 1st April 2018)

Kord, Susanne, Murderesses in

German writing, 1720-1860: Heroines of Horror (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2009)- via Google Books

Leal, Amy, ‘‘Unnameable desires in

Le Fanu’s Carmilla’’, http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/Leal-names-desire-Carmilla.pdf

(Accessed 2nd April 2018)

Le Fanu, Joseph Sheridan, ‘‘Carmilla’’ (Bizarro Press, 2012)

Myers, Wade C., Burket, Roger C.,

Husted, David S., ‘‘Sadistic Personality Disorder and Comorbid Mental Illness

in Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients’’, Journal

of the American Academy pf Psychiatry and the Law Online https://archive.is/20130415045910/http://www.jaapl.org/content/34/1/61.full.pdf.html

(Accessed 29th March 2018)

Pizarnik, Alejandra, La

Condesa Sangrienta, http://ral-m.com/revue/IMG/pdf_Pizarnik_Alejandra_-_La_Condesa_Sangrienta.pdf

(Accessed 28th March 2018)

Singer, June, Culture

and the Collective Unconscious (Illinois: Northwestern University, 1968)-

via Google Books

Stoker, Bram, ‘‘The Squaw’’, http://www.bramstoker.org/pdf/stories/03guest/03squaw.pdf

(Accessed 28th March 2018)

Stupak, Valeska C. and Ronald J.,

‘‘Carl Jung, Feminism, and Modern Structural Realities’’, International Review of Modern Sociology, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Autumn 1990), pp. 267-276 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41421571?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

(Accessed 1st April 2018)

Tatar, Maria, The

Classic Fairy Tales (Second Edition) (Norton Critical Editions) (New York:

W.W. Norton&Company, 2017)-via Google Books

Thorne, Tony,

Countess Dracula (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1997)- via Google Books

Torture Museum, ‘‘ The Nuremberg Virgin’’, http://torturemuseum.net/en/the-nuremberg-virgin/

(Accessed 4th April 2018)

IMAGES:

Portrait of Elizabeth Báthory, http://crimefeed.com/2016/12/crime-history-countess-elizabeth-bathorys-blood-crimes-come-to-light/

Illustration of Snow White’s Stepmother by P.J.Lynch http://www.pjlynchgallery.com/book-illustration/mirror-mirror-on-the-wall/

Illustration

by Carlos Schwabe for Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fleurs-du-mal_tonneau.jpg

Illustration from Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘‘Carmilla’’ by

D.H.Friston, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmilla#/media/File:Carmilla.jpg

Elizabeth Báthory by István Csók, https://www.paintingstar.com/item-erzsebet-bathory-sketch-s116598.html

Illustration by Santiago Caruso for Alejandra Pizarnik’s

text, http://birthofparadise.tumblr.com/post/67902937149/countess-erzs%C3%A9bet-b%C3%A1thory-de-ecsed-born-august

Goya’s etching, Pretty

Teacher!, https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/pretty-teacher/50d8b8e8-61c8-4e83-ab16-3efc9dedf0f9